There was a fantastic tale in The New Yorker a few weeks back about the discovery of legendary riches at the Sri Padmanabhaswamy temple in India. Two ancient vaults were to be opened. The first held an estimated twenty billion dollar hoard of gold and jewels that an eyewitness described as "stars glittering on a night when there is no moon." The other, a supposed treasury for gold bars, had a faulty lock and remained closed. Despite the staggering wealth of the first vault, there has been no rush to open the second, and many locals are insisting that the treasure be sealed back up and left in place.

After reading all sorts of variations on Bluebeard to prepare for book club next week, a story where a locked door stays locked was peculiarly nice. We hide plenty of awful things in forbidden rooms, but a locked door can also be a refuge.

In more radical Bluebeard re-imaginings, the forbidden chamber becomes a symbol for what Justine Jordan calls "the elusive authentic self" preserved against the pressure of outside curiosity. Locking those selves away used to be the preferred m.o. Now, like Bluebeard's bride, our ruling mania is exposure. We throw open whatever doors we can and invite everyone in. It isn't always a bad thing. Light can cleanse and empower, shrink all sorts of fears and dreads, reduce terrors to commonplaces, give the lonely a community.

In more radical Bluebeard re-imaginings, the forbidden chamber becomes a symbol for what Justine Jordan calls "the elusive authentic self" preserved against the pressure of outside curiosity. Locking those selves away used to be the preferred m.o. Now, like Bluebeard's bride, our ruling mania is exposure. We throw open whatever doors we can and invite everyone in. It isn't always a bad thing. Light can cleanse and empower, shrink all sorts of fears and dreads, reduce terrors to commonplaces, give the lonely a community.

Still, what we share is self-report. It's a product of calculation — as it should be. Overexposure is corrosive. T.S. Eliot was on to something:

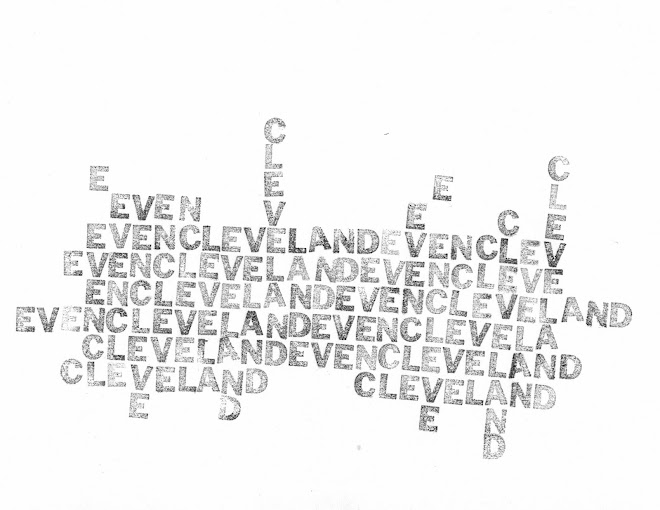

All significant truths are private truths. As they become public they cease to become truths; they become facts, or at best, part of the public character; or at worst, catchwords.At some point, all the various accumulations of personal miscellany and the telling details of our lives we share stop being treasure. Moving through the world, we cast shadows and leave fingerprints. Those are the interesting traces. We reveal plenty without ever intending to.

I like the idea of the locked door; not to hide the terrible, but to protect the precious. I'm glad it's there.